Political instability in Italy is nothing new. Since 1980, the country has run through 23 prime ministers; by contrast, the UK has had just six. However, the latest developments imply a new level of political chaos.

Since the election in March, the Five Star Movement and the Northern League have come together from opposite ends of the political spectrum to form a programme for government. Despite their differences, they have coalesced around a radical plan centred on an overhaul of the tax system and a universal basic income that has been costed at around EUR65 billion per annum. At 5% of GDP, that is clearly incompatible with either European rules or basic fiscal sanity.

By imposing a veto on the coalition's first choice of finance minister, the Italian president threatened to quash the government before it even took office. The parties have tried again with a new candidate, but considerable political uncertainty still looms large over Italian and European markets.

Until a few months ago, the average interest rate payable on newly issued Italian debt was just 20bp (i.e. 0.2% … that is not a typo). The market is now rapidly reassessing whether that was a sensible reflection of credit risk.

Investors have taken fright at the reincarnation of political risk: Italian bond yields have snapped higher by over 100bps in the last month, as at the time of writing, and the Italian equity market is down around 10% over the same time. Inevitably, this situation evokes unpleasant memories of the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis. On a risk-neutral* basis, the market-implied probability of Italian default over the next five years has jumped to around 20%.

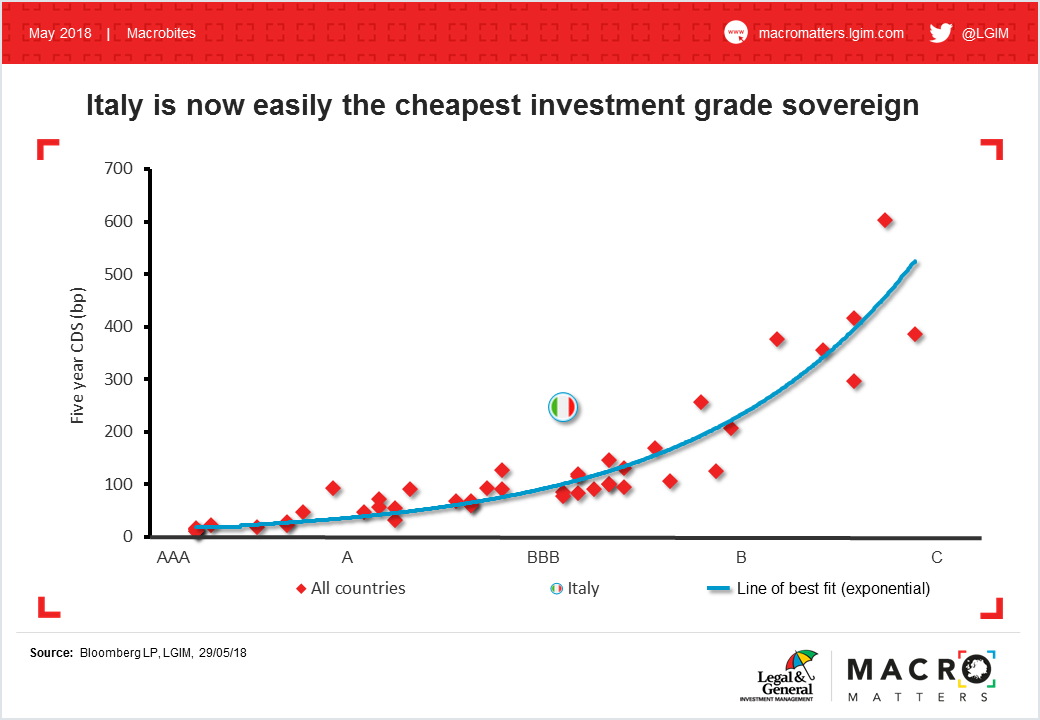

Italian government debt has become a clear outlier, with the market now demanding a significant premium for holding it relative to any other investment grade-rated sovereign (see chart below). That is despite €4 billion per month of purchases by the European Central Bank (ECB) under its asset purchase programme.

The situation is fast-moving, and despite the recent easing of some investor concerns, it definitely still has the potential to turn toxic. Italian public debt outstanding is close to €2 trillion. That is larger than the public debt markets in Germany, France or the UK. In comparison, Greek public debt peaked at around €350 billion in 2011.

Greek default gave the European financial system serious chest pains; but an Italian default would give it a heart attack.

Italy, therefore, looks like an archetypal 'too big to fail' borrower.

However, if Italy were to descend into genuine financial trouble, the European and global bailout funds would be stretched to breaking point. Greece, Ireland and Portugal were locked out of financial markets after their bailouts. The public sector therefore had to assume their gross financing needs for several years and underpin their banking systems.

Italy’s gross financing needs are close to €400 billion per annum. That compares to unused lending capacity for the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the Eurozone's bailout fund, of €380 billion. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has only around €1 trillion of available resources. For any institution other than the ECB, with its potentially infinite balance sheet, Italy is therefore also 'too big to bail'. Yet the central bank is adamant that for legal reasons, it cannot own more than 33% of a Eurozone country’s outstanding debt – and it already owns around 16% of the Italian debt pile. The monetary guardian also insists that if Italy were to be downgraded to junk by four ratings agencies (Moody's, S&P, Fitch and DBRS), it would have to stop its bond purchases.

So to say the situation is precarious is something of an understatement.

Before letting the deepest and darkest fears overwhelm us, it is worth emphasising how solidly (yes, solidly) Italian finances have been managed in the last few years.

The average primary government surplus of Italy – which excludes debt servicing costs – over the last decade has been +1% of GDP. Of the 35 countries in the OECD, only Norway (due to its vast oil wealth) has been more disciplined. On that measure, Italy’s fiscal prudence has been even stronger than Germany’s.

Similarly, the health of the banking system has improved markedly, with non-performing loans down by over 25% since 2015.

Bulwarks against fiscal craziness are also embedded in the Italian constitution: reforms came into force in 2014 that amended several of its articles with a set of balanced budget provisions. Those are outlined in the box below.

|

Will those defences hold if the government is adamant on blowing things up? We simply don’t know as they have never been tested in the Constitutional Court. But the recent intervention of President Sergio Mattarella suggests he takes his oath to "uphold the Constitution" pretty seriously. It is also worth noting that the septuagenarian president commands significantly more public trust than any other politician, with approval ratings above 65% compared to less than 40% for the party leaders.

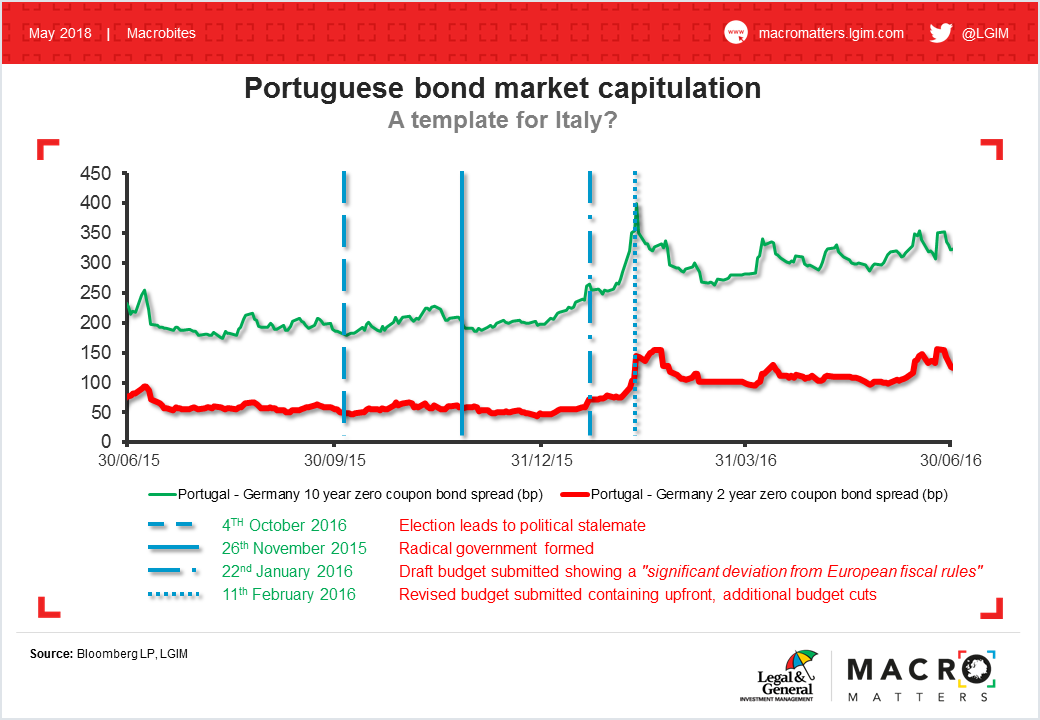

Through all this, we should recall the example of Portugal (see chart below). The Portuguese people elected a government with a radical economic agenda in late 2015; financial stress peaked around three months after the formation of the government. The catalyst for the final blow-up (and subsequent Portuguese capitulation) was a clash with Europe over Portugal’s budget.

In an interesting twist, the head of the Eurogroup (the committee of Eurozone finance ministers who represent “the authorities” in this instance) is now the Portuguese finance minister who went through that capitulation, Mário Centeno. Having been down the road to Damascus himself, it’s hard to imagine he’s going to be particularly sympathetic to Italian demands for much looser fiscal policy.

Where does that leave us? There’s a debate within LGIM about the systemic implications of Italy being pushed to the brink. European banks, France, the euro, and Brexit negotiations are all likely to be in serious trouble in that event. However, we also recognise that Italian risk is now attractively priced relative to other countries.

Within the asset allocation team, we are looking for yield spread-widening comparable to that seen in Portugal a few years ago to add Italian risk in our portfolios. In the near-term, matters are likely to come to head in the autumn. Like all euro-area countries, Italy has to submit a draft budget for scrutiny by the European Commission by mid-October. That is a significant potential flashpoint given the gap between the new government's campaign rhetoric and EU fiscal rules.

However, sooner or later, matters are set to come to a head with a return to the ballot box. Those elections are likely to be seen as a proxy vote on Italy’s place in Europe. The recently published Eurobarometer survey highlights the paradox at the heart of Italian public opinion: just 39% are willing to say that Italy’s membership of the EU is a “good thing”, but 59% are in favour of the single currency.

Until that ambivalence is put to the test, it is financial markets that are likely to provide the strongest pushback against radicalism.

* A footnote on risk-neutral probabilities is probably worthwhile. 20% might seem like a scarily high number, but it is important to realise that this is not the same as a real world probability because investors are risk averse. The risk-neutral probability is derived from credit default swaps (CDS) under the assumption that there is no compensation for risk embedded in the price and the recovery rate in the event of default is 40%. For BBB-rated debt, such as Italy, the historical record is consistent with the genuine default probability being around five times smaller than the risk-neutral probability.